After earning a Fulbright Fellowship in 2013, Kristin Van Busum was determined to help small-scale coffee growers in Nicaragua tap into the global coffee market and improve their quality of life.

Van Busum, an Indianapolis native who left a cushy job at a Boston think tank, said despite her good intentions, her plans quickly unraveled. Although she made inroads into the coffee-growing community, her initiative failed to launch.

“When I went down there, I ended up building strong relationships in the community, collected a lot of data and the project completely failed,” she said. “It was humiliating form me and it didn’t work. I was a one-woman show, and the coffee trade is complex and there is a lot of corruption.”

Although her original plan was kaput, Van Busum said one thing stood out during her travels: the children of coffee plantation workers. Their lack of education — most never receive schooling past sixth grade — stood out as an area where Van Busum knew she could make a difference.

Children often are left at home while their parents work in the fields, Van Busum said. Instead of going to school, they’re tasked with taking care of siblings, doing chores and preparing food.

“Kids don’t even feel good — there’s all these environmental issues facing children,” she said. “Schools are far away, they are difficult to access and teachers are untrained or unpaid.

“Even if there is a school structure, there is no good teaching in the community.”

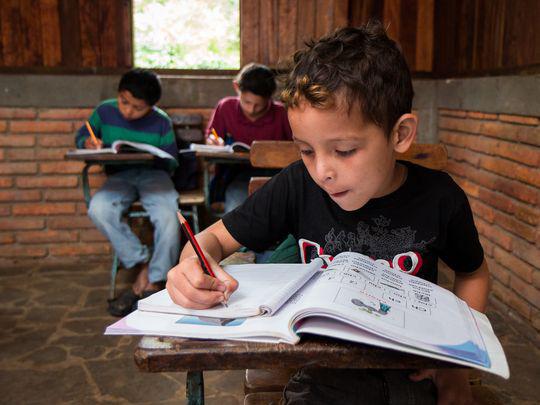

That need inspired Van Busum to create Project Alianza, a nonprofit organization that has opened two schools on coffee plantations in Nicaragua. The project, formed in 2014, teaches about 300 children a year and aims to increase that reach.

The schools operate similarly to American elementary schools. Children who are able to attend year after year — some may receive partial schooling because their parents are migrant workers — can receive consistent education through the sixth grade.

“They all need access to school,” Van Busum said. “Their families earn like $3 a day. There are incredibly low resources, and they don’t have much of anything.”

Rick Peyser, a Project Alianza board member with almost three decades of experience in the coffee industry, said the children of coffee workers are in desperate need of education. Children suffer and are trapped in poverty because they’re never formally educated, he said.

“Often times, children are the youngest and least able to communicate with the farm management and are often forgotten,” he said.

Something like Project Alianza, which brings schooling to a coffee plantation, is invaluable, Peyser said.

“It’s a gift that will ultimately lift that child, that child’s family and the country up,” he said. “Supporting educational opportunity is a way to lift many areas out of poverty. It takes a long time.”

Peyser said he was impressed with Project Alianza’s dedication to providing a quality education; it’s the main reason he joined the board. Peyser said his career with Keurig Green Mountain, formerly Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, made him passionate about bettering the lives of coffee plantation workers.

“Unlike here in the United States, access to fundamentals like education are not something you can take for granted,” he said.

Tania Ferrufino, who owns a coffee plantation in Nicaragua with her brother, said educating children is essential to breaking the cycle of poverty. A lot of the potential children have is wasted if they’re not given a formal education, she said.

Ferrufino said she welcomed Project Alianza to her large-scale farm because she already was exploring the possibility of opening a school.

“Before meeting Kristin, my family had been trying to set up the school at Finca Aurora for a few years, but it had become hard to supervise and develop a formal educational structure because most teachers were only transitional and we had no system to hold them accountable,” she said. “When we met Kristin, we were extremely moved by her motivation and very impressed by her and the Project Alianza team.”

Project Alianza betters the lives of coffee workers and their families, which is an issue more farm owners should be concerned with, Ferrufino said. The program is able to seamlessly incorporate national educational standards into its work, which was one of the difficulties Ferrufino faced when she considered opening a school.

“We were finally able to work with a team that was in charge of the school on a daily basis and that had experience on how the educational structures in the country worked,” she said. “Their expertise and strong work ethic has made in a big difference in the lives of the children and their families.”

Van Busum has received support in the Indianapolis community for her work. Stephen Hall, co-founder of Tinker Coffee Co., said he has thrown fundraisers for Project Alianza because he supports its mission. Although the north-side shop doesn’t carry any of the coffee grown on the farms Van Busum works with, Hall said he’s hopeful they will in the future.

“Coffee has this connection to the global economy that we appreciate and understanding the challenges people face at the farm level is captivating to us and supports our mission of making the world a better place through coffee,” Hall said.

Van Busum said she wants to expand Project Alianza to 10 schools and beyond Nicaragua’s borders. The goal is to make education the norm, she said.

“I want to see every child in the coffee lands get access to school,” she said, adding that 300,000 children in the region are laborers. “Really, the end goal is to make education the norm in these communities and not have parents question whether they should put their kids in school.”

Source: Indy Star

FR

FR EN

EN AR

AR