Text of the article 37

States Parties shall ensure that:

(a) No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without possibility of release shall be imposed for offences committed by persons below 18 years of age;

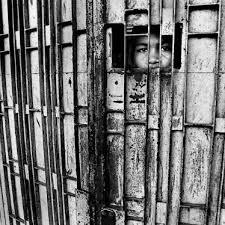

(b) No child shall be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily. The arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time;

(c) Every child deprived of liberty shall be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, and in a manner which takes into account the needs of persons of his or her age. In particular every child deprived of liberty shall be separated from adults unless it is considered in the child's best interest not to do so and shall have the right to maintain contact with his or her family through correspondence and visits, save in exceptional circumstances;

(d) Every child deprived of his or her liberty shall have the right to prompt access to legal and other appropriate assistance, as well as the right to challenge the legality of the deprivation of his or her liberty before a court or other competent, independent and impartial authority, and to a prompt decision on any such action.

What does article 37 say?

Article 37 mainly addresses issues relating to children in conflict with the law (or ‘youth justice’). It refers to a number of rights:

- No child shall be subjected to torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment

- No child should be unlawfully arrested or detained.

- Both capital punishment and life imprisonment without the possibility of release are prohibited for offences committed by persons below 18 years.

- Any detained child must be separated from adults unless it is considered in the child's best interests not to do so.

- A child who is detained shall have legal and other assistance as well as contact with the family.

Article 40, on the administration of juvenile justice, is especially relevant for the fulfilment of article 37.

Why is this right important?

Article 37 contains a number of different, important provisions that deserve individual mention.

- The prohibition of torture

UNICEF says that the torture of children “occurs in different contexts, including police operations against children seen as a threat to public order or safety; children confined in prisons or detention facilities; and children seen as linked to subversive groups, including the children of militants” (O’Donnell and Liwski 2010: 28). Police forces may also use torture to extract information and confessions. Non-physical punishment that “belittles, humiliates, denigrates, scapegoats, threatens, scares or ridicules the child” is cruel and degrading and incompatible with the CRC (Committee on the Rights of the Child’s 2006 General Comment)

The prohibition of torture is an absolute right – this means that it cannot be derogated from, or excused for, any reason. Torture, as opposed to abuse, is committed by an agent of the state for a specific reason, and causes severe pain or suffering.

- Deprivation of liberty

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has noted that detention causes serious harm to children (see above link, p.5). Importantly, Article 37 (b) explicitly provides that deprivation of liberty, including arrest, detention and imprisonment, should be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time, so that the child’s right to development is fully respected and ensured.

The lawful arrest or detention of children can only take place under certain circumstances. It must be proportionate and only carried out in certain situations, including, for example, detention following court conviction; arrest or detention for failing to observe a court order/legal obligation; and arrest or detention on remand (when due to come before a court) (see also the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (article 9 onwards).

- Capital punishment and life imprisonment without the possibility of release

These sentences are prohibited for offences committed by persons below 18 years. However, research suggests that in at least seven States, child offenders can lawfully be sentenced to death by lethal injection, hanging, shooting or stoning. In some States, children as young as 10 can be sentenced to life imprisonment. In at least 40 States, children can still be sentenced to whipping, flogging, caning or amputation.

- A detained child must be separated from adults

Much research has concluded that the placement of children in adult prisons or jails compromises their basic safety, well-being, and their future ability to remain free of crime and to reintegrate.

- A child who is detained shall have legal and other assistance as well as contact with the family.

Every child deprived of liberty has the right to maintain contact with his/her family through correspondence and visits. The child should be placed in a facility that is as close as possible to his/her family. The staff of the facility should promote and facilitate frequent contacts of the child with the wider community

- Representation and participation

It is the responsibility of the authorities (e.g. police, prosecutor, judge) to make sure that the child understands each charge brought against him/her. The provision of this information to the parents or legal guardians should not be an alternative to communicating this information to the child.

The child must be guaranteed legal or other appropriate assistance in the preparation and presentation of his/her defence.

What are the problems?

Particular groups of children may be vulnerable to having their Article 37 rights violated. For example, children in institutional care in many countries are subject to violence from staff and others responsible for their wellbeing. Children from ethnic minorities and/or deprived backgrounds may be particularly vulnerable to arrest and detention, or to disproportionate police attention.

In general, social and cultural approaches to children and childhood can create barriers to understanding the rights of children in conflict with the law. If children are understood as the property of parents or the State, or as persons with ‘mini rights’, it becomes more difficult to appreciate that they are entitled to, for example, access to legal representation or rights to due process.

Impunity, and lack of proper investigation into allegations of torture, or into lack of due process and regard to child welfare in the juvenile justice process, all act as impediments to the realisation of children’s rights.

What should States do about it?

The best interests of the child must be the primary concern in any justice proceedings. In the case of allegations of torture or other harmful treatment, the obligation to bring torturers to justice in order to prevent impunity must be reconciled with the right of child victims to psychological recovery. The Committee on the Rights of the Child, in its Concluding Observations to States, points out gaps in national legislation, and encourages governments to ratify the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) where they have failed to do so.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child, in its General Comment on juvenile justice, includes a number of recommendations for States to abide by.

Source: Crin

FR

FR EN

EN AR

AR