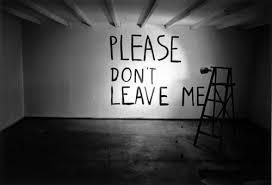

Child abandonment is the leaving of a child on his or her own without any intention of returning to ensure their safety and wellbeing. Causes include many social and cultural factors as well as mental illness. Abandonment of a child is considered to be a serious crime in many jurisdictions. For example, in the US state of Georgia, it is illegal to ‘wilfully’ and voluntarily abandon a child.

In a recent study of Western European countries (Belgium, France, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and the UK), which provided information on reasons for placing children under three in residential care institutions, abandonment was cited in four per cent of cases. In central and southeastern Europe (Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Romania and Slovakia), abandonment was cited in 32 per cent of cases. In Brazil, a national survey of 589 institutions receiving federal funding revealed that18 per cent of children had been institutionalised because of abandonment .

Reasons for abandonment may be complex, and vary from country to country, as well as over time. For example, in 1972, a Belgian committee found three motives for abandonment: 1) when a mother finds herself pregnant and is left by the father of the baby; 2) where mothers have very poor social and moral adjustment in early life, and have difficulty in accepting responsibility; and 3) when married women abandon their babies born from extramarital affairs. Yet these motivations will have changed over time according to shifting morals, such as less stigma attached to extramarital affairs, and evolving welfare provision in Belgium. However, one motivation that has been a consistent cause of abandonment over time is poverty. Inadequate social welfare systems mean that those not financially capable of taking care of a child are more likely to abandon him/her. Overcomplicated or inaccessible adoption proceedings are also likely to increase the likelihood of child abandonment, while a shortage of alternative care institutions to take in children whose parents cannot support them is also likely to increase the risk. Societies with strong social structures and liberal adoption laws tend to have lower rates of child abandonment. Disabled children, in particular, are at higher risk of abandonment – and this practice may be socially accepted and even encouraged (UN, 2005). ‘Exposure’, essentially a breed of infanticide, is also a form of abandonment whereby children are left outside in a place where they are unlikely to be discovered by others.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child, in its Concluding Observations to States, has made frequent reference to abandonment. For example, in 2003 it noted the “ejection” or abandonment of twins in the Mananjary region of Madagascar. And in its 2005 report to Nicaragua, it noted the “difficulties that some parents and families encounter - such as unemployment, malnutrition and lack of adequate housing - which may cause abandonment or abuse resulting in the placement of children in institutions or for adoption.”

What can be done about it?

The UN Study on Violence Against Children calls on governments to reduce rates of abandonment and institutionalisation by “ensuring parents’ access to adequate support, including services and livelihood programmes. Priority should be given to supporting families of children with disabilities, and other children at high risk of abandonment or institutionalisation.”

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has made a number of recommendations to States regarding abandonment. In 2003, in its Concluding Observations to Bangladesh, it asked the government to “take effective measures to prevent abandonment of children, inter alia, by providing adequate support to families.”

In 2001, it asked Lesotho to “strengthen enforcement of maintenance orders and pay special attention to providing families in need with adequate support including training and empowerment of parents in order to prevent abandonment of children.”

And in 2003, in Concluding Observations to Italy, it pressed the government to “urgently review and amend legislation in order to ensure that children born out of wedlock legally have a mother from birth (in accordance with European Court on Human Rights' decision Marckx v. Belgium and the rule mater semper certa est) and encourage recognition of these children by their fathers (as a way to prevent "easy" abandonment of children).”

Source: CRIN

FR

FR EN

EN AR

AR